Alzheimer's disease: Mystery of dying brain cells solved

About 55 million people live with dementia worldwide. It is estimated that the number of dementia cases will grow to about 139 million by the year 2050.

September 7, 2024

About 55 million people worldwide live with some form of dementia — of which Alzheimer's is just one such disease.

Two-thirds of people with dementia live in developing countries.

As the global population ages, it is estimated that the number of dementia cases will grow to about 139 million by the year 2050. People in China, India, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa are likely to be worst hit.

Researchers have been looking for medical treatments for Alzheimer's for decades, but their successes have been limited.

There has been new hope, however, since the discovery of an active agent called Lecanemab.

The drug was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2023 and shows signs that it slows the development of Alzheimer's in its early stages.

Complex processes in the brain

It's been challenging to develop medicines against Alzheimer's because researchers have yet to fully understand what happens in the brain when the disease takes hold.

One of the most pressing questions is why brain cells die.

Researchers know that amyloid and tau proteins develop in the brain, but until recently, they did not know how they function together or influence cell death.

But researchers in Belgium and the UK say they can explain what's happening now.

Mystery of cell death solved

According to a study published in the journal Science, the researchers say there is a direct connection between these abnormal proteins, amyloid and tau, and what's called necroptosis, or cell death.

Cell death usually happens as an immune response to infection or inflammation and rids the body of undesirable cells. That enables new, healthy cells to grow.

When the supply of nutrients collapses, the cells swell up, destroying a plasma membrane. The cells get inflamed and die off.

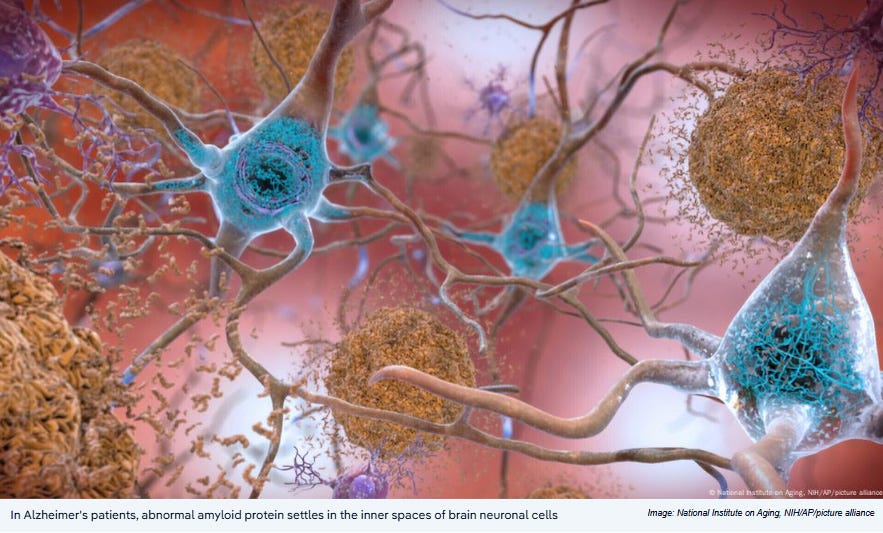

In the study, the researchers suggest that cells in Alzheimer's patients get inflamed when amyloid protein gets into neurons in the brain. That changes the internal chemistry of the cells.

The amyloid clumps into so-called plaques, and the fiber-like tau protein forms its own bundles, known as tau tangles.

When these two things happen, the brain cells produce a molecule called MEG3.

The researchers attempted to block MEG3 and said that the brain cells survived when they could block it.

To do this, the researchers transplanted human brain cells into the brains of genetically modified mice, which produced a large amount of amyloid.

One of the researchers, Bart De Strooper of the Dementia Research Institute in the UK, said it was the first time after three to four decades of speculation that scientists had found a possible explanation for cell death in Alzheimer's patients.

Hope for new medicines

The researchers, based at KU Leuven in Belgium and the Dementia Research Institute of University College London, said they hope their findings will help in the discovery of new medical treatments for Alzheimer's patients.

Their hope is not without good reason: the drug Lecanemab explicitly targets the protein amyloid. If it's possible to block the MEG3 molecule, medicine may manage to stop cell death in the brain altogether.

This article was originally published in German.